Table of Contents

TogglePower quality issues of solar energy system integrated into the grid

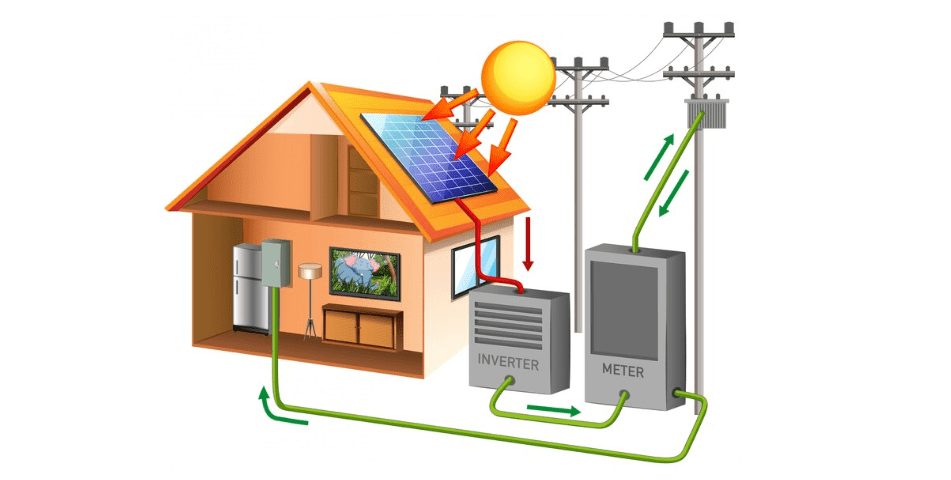

A grid-connected PV (photovoltaic) power system is electricity generating solar PV power system that is connected to the utility grid. A grid-connected PV system consists of solar panels, one or several inverters, a power conditioning unit and grid connection equipment. They range from small residential and commercial rooftop systems to large utility-scale solar power stations.

Unlike stand-alone power systems, a grid-connected system rarely includes an integrated battery solution, as they are very expensive. When conditions are right, the grid-connected PV system supplies the excess power, beyond consumption by the connected load, to the utility grid.

Solar energy gathered by photovoltaic solar panels, intended for delivery to a power grid, must be conditioned, or processed for use, by a grid-connected inverter. An inverter changes the DC input voltage from the PV to AC voltage for the grid.

This inverter sits between the solar array and the grid, draws energy from each, and may be a large stand-alone unit or may be a collection of small inverters, each physically attached to individual solar panels. The inverter must monitor grid voltage, waveform, and frequency. One reason for monitoring is if the grid is dead or strays too far out of its nominal specifications, the inverter must not pass along any solar energy.

An inverter connected to a malfunctioning power line will automatically disconnect in accordance with safety rules. Another reason for the inverter monitoring the grid is because for normal operation the inverter must synchronize with the grid waveform, and produce a voltage slightly higher than the grid itself, in order for energy to smoothly flow outward from the solar array.

In general, grid connected PV systems are installed to enhance the performance of the electric network; PV arrays (as well as other distributed generation (DG) units) provide energy at the load side of the distribution network, reducing the feeder active power loading and hence improving the voltage profile. As a result, PV systems can delay the operation time of shunt capacitors and series voltage regulators, thus increasing their lifetime.

PV systems can also reduce the losses in distribution feeders if optimally sized and allocated. PV systems can increase the load carrying capability (LCC), which is the amount of load a power system can handle while satisfying certain reliability criteria, of existing networks.

To meet increased demand while satisfying the same reliability criteria, utilities have to increase their generation capacity However, PV systems can also impose several negative impacts on power networks, especially if their penetration level is high. These impacts are dependent on the size as well as the location of the PV system.

PV systems are classified based on their ratings into three distinct categories:

(1) Small systems rated at 10 kW or less,

(2) Intermediate systems rated between 10 kW and 500 kW, and

(3) Large systems rated above 500 kW.

The first two categories are usually installed at the distribution level, as opposed to the last category which is usually installed at the transmission/sub-transmission levels.

Large-scale PV systems( More than 500 KW)

The anticipated impacts of large-scale PV systems (above 500 kW) on transmission/sub-transmission networks are as follows:

Severe power, frequency, and voltage fluctuations

PV arrays’ output is unpredictable and is highly dependent on environmental conditions such as temperature and insolation levels as depicted in Fig.no.4 and 5, respectively. Partial shading due to passing clouds, temperature, and insolation random variations are all factors that will affect PV system production, resulting in rapid fluctuations in its output power.

In a practical study on a 2 MW solar plant on a distribution feeder, the power output was measured and recorded every 5 min. The measurements showed sudden and severe power fluctuations caused by passing clouds and morning fog. Active power fluctuations result in severe frequency variations in the electrical network, whereas reactive power fluctuations result in substantial voltage fluctuations. These voltage fluctuations may cause nuisance switching of capacitor banks.

Increased ancillary services requirements

Since the grid acts as an energy buffer to compensate for any power fluctuations and firm up the output power of PV sources, thus, generating stations’ outputs need to be adjusted frequently to cope with the PV power fluctuations, i.e., to dance with the sun.

For example, if a cloud blanked out a PV system supplying 1 MW of electricity in 10 s, then the electric grid should be able to inject extra power at a rate of 1 MW/10 s or else voltage and frequency disturbances will occur in the power system.

As a result, utilities need to incorporate fast ramping power generation to compensate for these power fluctuations from PV arrays before voltage and frequency variations exceed the allowable limits. The previous situation also necessitates a significant increase in the frequency regulation requirements at higher penetration levels of PV systems.

The frequency regulation should increase by 10%. Geographical distribution of PV arrays in a certain region plays an important role in deter-mining the maximum allowable PV penetration in that region; the closer those PV arrays are, the more power fluctuations are expected due to clouds, and the more frequency regulation service is needed to balance out those power fluctuations.

1.3% if the PV system is located at a central station.

6.3% if the PV system is located in 10 km2 area.

18.1% if the PV system is located in 100 km2 area.

35.8% if the PV system is located in 1000 km2 area.

These results indicate that, due to their dispersed nature, small scale PV systems are not likely to impact frequency regulation requirements and so, these requirements should be deter-mined based on the penetration level of large, centralized PV stations only.

Stability problems

PV arrays’ output is unpredictable and is highly dependent on environmental conditions. This unpredictability greatly impacts the power system operation as they cannot provide a dispatch able supply that is adjustable to the varying demand, and thus the power system has to deal with not only uncontrollable demand but also uncontrollable generation. As a result, greater load stability problems may occur.

PV arrays do not have any rotating masses; thus, they do not have inertia and their dynamic behaviour is completely controlled by the characteristics of the interfacing inverter. As the penetration level of PV increases, more conventional generators are being replaced by PV arrays; thus, the damping ratio of the system increases.

As a result, the oscillation in the system decreases. The presence of solar PV generation also can change the mode shape of the inter-area mode for the synchronous generators those are not replaced by PV systems. Some critical synchronous generators should be kept online (even if they are operating beyond their economic operating range) to maintain sufficient damping of the system. During fault conditions in a system with high PV penetration, rotors of some of the conventional generators swing at higher magnitudes.

The study on the impacts of large-scale PVs on voltage stability of sub-transmission systems concluded that PV sizes, locations, and modes of operation have strong impacts on static voltage stability; voltage stability deteriorates due to PV inverters operating in constant power factor mode of operation, whereas PV inverters operating in the voltage regulation mode may improve the system voltage stability.

Small/Medium PV systems (below 500 kW)

The anticipated impacts of small/medium PV systems (below 500 kW) on distribution networks are as follows:

Excessive reverse power flow

In a normal distribution system, the power flow is usually unidirectional from the Medium Voltage (MV) system to the Low Voltage (LV) system. However, at a high penetration level of PV systems, there are instants when the net production is more than the net demand (especially at noon), and as a result, the direction of power flow is reversed, and power flows from the LV side to the MV side.

This reverse flow of power results in overloading of the distribution feeders and excessive power losses. Reverse power flow has also been reported to affect the operation of automatic voltage regulators installed along distribution feeders as the settings of such devices need to be changed to accommodate the shift in load centre. Reverse power flow may have adverse effects on online tap changers in distribution transformers especially if they are from the single bridging resistor type.

Over voltages along distribution feeders

Reverse power flow leads to over voltages along distribution feeders. Capacitor banks and voltage regulators used to boost voltage slightly can now push the voltage further; above the ac-acceptable limits. Voltage rise on MV networks is often a constraining factor for the widespread adoption of wind turbines. Voltage rise in LV networks may impose a similar constraint on the installation of PV systems. This problem is more likely to occur in electrical networks with high penetration of dispersed PV power generation.

Increased difficulty of voltage control

In a power system with embedded generation, voltage control becomes a difficult task due to the existence of more than one supply point. All the voltage regulating devices, i.e., capacitor banks and voltage regulators, are designed to operate in a system with unidirectional power flow.

Increased power losses

DG systems reduce system losses as they bring generation closer to the load. This assumption is true until reverse power flow starts to occur. Distribution system losses reach a minimum value at a penetration level of approximately 5%, but as the penetration level increases, the losses also increase and may exceed the no-DG case.

Severe phase unbalance

Inverters used in small residential PV installations are mostly single phase inverters. If these inverters are not distributed evenly among different phases, phase unbalance may take place shifting the neutral voltage to unsafe values and increasing the voltage unbalance.

Power quality problems

Power quality issues are one of the major impacts of high PV penetration on distribution net-works; power inverters used to interface PV arrays to power grids are producing harmonic currents; thus, they may increase the total harmonic distortion (THD) of both voltage and currents at the point of common coupling (PCC).Voltage harmonics are within limits if the network is stiff enough with low equivalent series impedance.

Current harmonics, on the other hand, are produced by high pulse power electronic inverters and usually appear at high orders with small magnitudes. An issue with higher-order current harmonics is that they may trigger resonance in the system at high frequencies. Diversity effect between different current harmonics can also reduce the overall magnitude of those current harmonics.

Another power quality concern is the inter-harmonics that appear at low harmonic range (below the 13th harmonic). These inter-harmonics may interact with loads in the vicinity of the inverter. Even harmonics (especially the second harmonics) can possibly add to the unwanted negative sequence currents affecting three phase loads. DC injections as well may accumulate and flow through distribution transformer, leading to a possible damage.

Increased reactive power requirements

PV inverters normally operate at unity power factor for two reasons. The first reason is that current standards (IEEE 929-2000) do not allow PV inverters to operate in the voltage regulation mode. The second reason is that owners of small residential PV systems in the incentive-programs are revenued only for their kilowatt-hour yield, not for their kilovolt-ampere hour production.

Thus, they prefer to operate their inverters at unity power factor to maximize the active power generated and accordingly, their return. As a result, the active power requirements of existing loads are partially met by PV systems, reducing the active power supply from the utility. However, reactive power requirements are still the same and have to be supplied completely by the utility.

A high rate of reactive power supply is not preferred by the utilities because in this case distribution trans-formers will operate at very low power factor (in some cases it can reach 0.6). Transformers’ efficiency decreases as their operating power factor decreases, as a result, the overall losses in distribution transformers will increase reducing the overall system efficiency.

Electromagnetic interference issues

The high switching frequency of PV inverters may result in electromagnetic interference with neighbouring circuits such as capacitor banks, protection devices, converters, and DC links leading to mal-function of these devices.

Difficulty of islanding detection

Islanding detection techniques are characterized by the presence of non-detection zones defined as the loading conditions for which an islanding detection method would fail to operate in a timely manner, and are thus prone to failure. Moreover, the inclusion of islanding detection devices increases the overall cost of integrating PV systems in electrical networks.

Interesting article about power quality challenges with grid-connected PV systems. I was researching similar issues and found some helpful visualizations on https://tinyfun.io/game/merge-one-piece that might be relevant to understanding the impact.

Hệ thống thanh toán của 888slot được tích hợp các công nghệ bảo mật hiện đại, đảm bảo rằng mọi giao dịch đều được mã hóa bảo vệ an toàn. Điều này giúp người chơi yên tâm thực hiện giao dịch mà không lo lắng về việc thông tin cá nhân hay tài khoản bị xâm nhập. Với hệ thống thanh toán nhanh chóng, an toàn và tiện lợi, nhà cái đã xây dựng lòng tin cùng sự hài lòng tuyệt đối từ cộng đồng người dùng. TONY01-29H